“But you don’t look sick” – the extra battle of Blackness by Maryann

October 18th, 2023

October 18th, 2023 Nakita Cambow

Nakita Cambow Blog

Blog 0 Comments

0 Comments

On the 7th of October LUPUS UK held an event in celebration of Black History Month (BHM). Alongside two consultant rheumatologists, they had guest speakers from the Caribbean and African Health Network (CAHN) who spoke about the importance of using Black History Month as an opportunity to discuss health issues within ethnic communities. I sat there discussing the experiences I had faced as a black woman needing medical assistance feeling tears leave my eyes as my experiences were echoed back, with the rheumatologist and other attendees acknowledging that I wasn’t alone in those challenges.

I had been asked to write about my experience as a black woman living with lupus last year, but declined as I had another topic that I wanted to focus on, but since writing my first draft of this article, I noticed a comment under the ad for the BHM event on Instagram asking what about white lupus warriors?, and it became apparent why I needed to speak about my personal experiences. As much as I would have loved to write a positive historical review of black pioneers in medicine, I feel there is still a disbelief about the disparities and implicit biases in medicine for Black, Asian, Hispanic and non-white ethnicities.

We know that lupus is three times more like to effect people of African, Caribbean heritage, and has a high prevalence in Asian and Hispanic heritages worldwide, but when you type “cutaneous lupus” or even just “lupus” into a google search, the images that are presented back are majority white skinned. So, for someone like me, who in 2018 was trying to find out if the lesions on my skin were related to my newly diagnosed condition, it took a while to find a suitable visual comparison. Why is this? Try it for yourself! You’ll see more images of cutaneous lupus in dogs (yes animals) then you will of lupus in black or brown people, surely there should be a balance? I’d have to Google “cutaneous lupus in black skin” to return reasonable images.

As the rheumatologist at the BHM event spoke of having to make a diagnosis for one of his patients by comparing pictures of what the patient looked like before to what they looked like during the appointment, it reminded me of times when I had to do the same thing. I’d have to show consultants pictures of myself before to prove that I was paler than normal, and that my skin was bruised or showing redness. I sat in the lecture theatre triggered but grateful for his honesty about the lack of training on what illnesses look like on dark/black skin.

He went on to speak about how studies have historically been carried out on white patients, and this is what our rheumatologists, dermatologists and GPs learn from. It leads to them not being able to recognise visual symptoms on people with non-white skin, which can lead to misdiagnosis not only of lupus but also for a range of medical conditions. It also means that symptoms escalate and are left to become severe before they’re treated. In the UK we know that black people are likely to have more severe symptoms, in America for Black/African and Hispanic women aged 15-44, Lupus is one of the top 10 causes of death, could that be down to the symptoms not being recognised early?

This problem is reflected in textbooks and other learning tools used by medical professionals. The issue is systemic and perhaps exacerbated by a lack of trust in medical professionals in ethnic communities whereby trials are not joined, and pictures are not taken, more likely due to historical experiences of abuse and non-consensual experimentation.

My way of helping to combat this issue was agreeing to be photographed by medical photographers during different stages of my skin flare, so that the images could be used for research purposes. I’m also in the process of licencing images of my skin during flare to a pharmaceutical company hoping to develop medication for patients with cutaneous lupus/discoid lupus (DLE) after speaking as a patient subject matter expert about CLE/DLE.

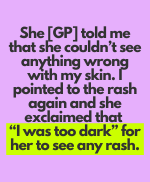

Prior to the lupus diagnosis, I was diagnosed with shingles after experiencing chills, pain, and noticing a blistery rash on my left arm. I saw a locum doctor after trying to get a GP appointment for over a week.  I spoke about my symptoms, how much pain my arm was in, how red it was, and attempted to show her the rash. She told me that she couldn’t see anything wrong with my skin. I pointed to the rash again and she exclaimed that I was too dark for her to see any rash. I stood up from the chair put my arm inches away from her face, and asked if she could see it now, at which point she ushered me away and told me not to touch anything as I could pass on chicken pox. I can’t even express the hurt I felt being told so callously that my dark-skinned complexion meant that I couldn’t be diagnosed. If I hadn’t of advocated for myself, I would’ve been sent home in pain, possibly suffering from the long-term effects of shingles such as nerve damage.

I spoke about my symptoms, how much pain my arm was in, how red it was, and attempted to show her the rash. She told me that she couldn’t see anything wrong with my skin. I pointed to the rash again and she exclaimed that I was too dark for her to see any rash. I stood up from the chair put my arm inches away from her face, and asked if she could see it now, at which point she ushered me away and told me not to touch anything as I could pass on chicken pox. I can’t even express the hurt I felt being told so callously that my dark-skinned complexion meant that I couldn’t be diagnosed. If I hadn’t of advocated for myself, I would’ve been sent home in pain, possibly suffering from the long-term effects of shingles such as nerve damage.

During a haematology appointment I was told that my low white blood count was caused by Ethnic Neutropenia, and that it was nothing to worry about because people of African/Caribbean and Asian descent are generally neutropenic. No check on my medical history was carried out to see if this was actually the case for me. I went back to my GP to compare past and present tests. It turned out that my white blood cell count in the past had been well within normal range and that the low white blood cell count was caused by the lupus and indicative of how sick I was. Making general assumptions like this, instead of looking at my personal medical history is medical bias. The whole reason why I was referred to a haematologist was to have a thorough investigation of my bloodwork which in this case was dismissed due to my ethnicity.

I was reading about why black and ethnic minorities were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and found a few studies discussing bias in medical equipment – in particular pulse oximeters not recognising black skin, resulting in inaccurate reading of blood oxygen levels. This may seem ludicrous, but I’ve experienced this in the medical and non-medical world (like the barriers at airports and the original Snapchat filters). I’m asthmatic so I’m used to having breathing issues, but I’ve experienced shortness of breath which we know is a symptom of SLE, which wasn’t asthma related (because I actually had pleurisy). I’ve sat in the consultant office struggling, trying to explain that my breathlessness isn’t down to me rushing or anxiousness, having to deal with the inconsistency of being told my blood oxygen result from the pulse oximeter is at 100% despite how I’m feeling (which doesn’t seem legitimate). It’s so draining.

Various studies in the US most notably one by Hoffman K.M et al (2016), and further studies as recent as 2020, found that over 40% of medical students still held beliefs (perpetuated during slavery) that black people had thicker skin, had less sensitive nerve endings and felt less pain than white people. These beliefs held by the medical students were found to influence the prescription of pain medication, with black patients being prescribed less pain treatment as compared to white patients, even when the patients were children. I’d love to say that this is just an America thing, but studies are now taking place in the UK after findings of racial bias. Again, I’ve had personal experience of this in London. My low tolerance for painkillers means I never go into hospitals requesting anything more than fluids and paracetamol but have been refused fluids on multiple occasions most recently in July when I attended A&E in severe pain due to my Raynaud’s activity. I was told to go home and drink water, which is almost impossible to do when fatigue wipes you out. I’ve also been told to get paracetamol over the counter when hospitals can prescribe stronger dosages.

When I’ve cried out due to hypersensitivity while being examined and having blood drawn, and been told off, told to stop making a fuss, despite me trying to explain that every touch felt like a punch. During a hospital stay in 2018 where I was admitted to an isolation room, the night nurse came to do my obs. I told her I couldn’t sleep due to pain asking for both paracetamol and ibuprofen. She told me that I don’t look like I’m in pain. I was told to choose either the ibuprofen or paracetamol, she refused to give me both, despite me being prescribed that combination by the Dr during the day. My pull cord wasn’t working and as I was in isolation, no one else was going to come and check on me so I went through the whole night in pain having been refused adequate pain relief.

I attended A&E 3 days consecutively due to extreme lower back pain which meant I was unable to walk properly, dizziness, nausea, and weakness. I was hypoglycaemic and the source of my pain was dismissed as being due to lupus. I was told I’d have to be seen by the rheumatologist but at the end of each day she was too busy to see me. On one of the days, which happened to be my birthday, I was left for over six hours lying on a bed waiting for the rheumatologist without being checked on, without any pain relief until my friend came and challenged them, the consultants excuse that I had said I have paracetamol at home fell short when my friend reminded them that I wasn’t actually at home. Even another patient’s visitor expressed disgust at how I was treated. On the third day I was sent home and asked to return later on in the day, but I received a call from the rheumatologist shouting at me, telling me to stop attending A&E, that pain was expected as I had lupus. A month later I received a blood form via first class post marked urgent. When I queried why, I was informed that results from a blood test taken during the times I had attended A&E showed that I had an infection, and they urgently needed to make sure that it was clear, and hadn’t escalated, and to give me antibiotics. In other words, I had every reason to be in A&E and my pain was real. I have many more incidents I could share but I’m truly exhausted.

Being a disease that affects non-white people at a higher rate, when only 18% of the UK is made up of non-white people, there is a known struggle for funding from government. It simply doesn’t affect a significant enough of the population. Which means that white lupus warriors end up being affected from the medical funding disparities as well. We must keep fighting and keep speaking up and raising awareness, so that funding is raised to hopefully one day find a cure.

All of us living with lupus regardless of our skin colour experience not looking sick but feeling awful, we’re not believed, must fight for answers and advocate for ourselves constantly, we all go through that. It’s just a lot tougher when the shade of your skin is a biological barrier.

If you wish to read more about studies and articles evidencing the history of the racial biases in medicine, the disparity findings please have a look at the list below:

- Covid: Pulse oxygen monitors work less well on darker skin, experts say – BBC News

- FDA warns pulse oximeters less accurate for people with darker skin | MobiHealthNews

- Skin Tone and Pulse Oximetry | Harvard Medical School

- In Focus: Black people are being failed by UK healthcare | Metro News

- How we fail black patients in pain | AAMC

- Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites | PNAS

- How False Beliefs in Physical Racial Difference Still Live in Medicine Today – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

- Why Don’t We Take Black People’s Pain Seriously? | Psychology Today

- Racism an issue in NHS, finds survey (bma.org.uk)

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)