Drug Therapy of Lupus

This site is intended for healthcare professionals as a useful source of information on the diagnosis, treatment and support of patients with lupus and related connective tissue diseases.

Introduction

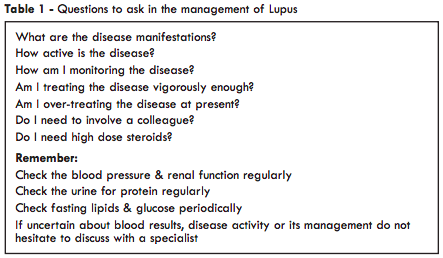

It would be wrong to sugest that the management of lupus is easy. The disease has numerous manifestations and each person has their own pattern of disease which can change over time, sometimes rapidly. In general, patients who present with severe lupus e.g. of the kidneys or central nervous system (CNS), and those with multiple autoantibodies tend to have persistent serious disease. Patients who present with mild disease may continue to have mild disease but, as time goes by, many will develop more serious manifestations, so it is important to consider whether any new symptom might represent a new manifestation of the disease.Treatment of specific disease manifestations is dealt with in the relevant chapters of this book so an overview of the drug management is given here. Treatment depends upon clinical assessment of the extent of organ involvement and also of its severity (Table 1).

Assessment of disease activity

Investigations are dealt with in detail elsewhere, however, clinical assessment of disease activity is as important as the results of laboratory tests. Tiredness, fever or mood disturbance can indicate a flare of disease, as well as more obvious manifestations such as rash or arthritis. Where there is significant internal organ involvement then appropriate tests can be used to monitor disease activity e.g. serum creatinine, eGFR, urinary protein or lung function tests. Otherwise, it is often possible to identify a test which reflects disease activity in an individual patient. This may be the DNA binding level, the serum C4 or C3 concentration, the white cell count, haemoglobin or, perhaps, even the ESR. Such combined clinical and laboratory assessment helps one to decide whether it is necessary to use more aggressive treatment or, alternatively, whether the dose of medication can be reduced.Various disease assessment indices have been developed e.g. BILAG, SLEDAI, SLAM & ECLAM and are used in specialist units. They variably assess disease activity and tissue damage and it can be difficult to distinguish the effects of currently active inflammation from those of established damage. Quality of life may also be assessed by measures such as the SF-36 questionnaire.

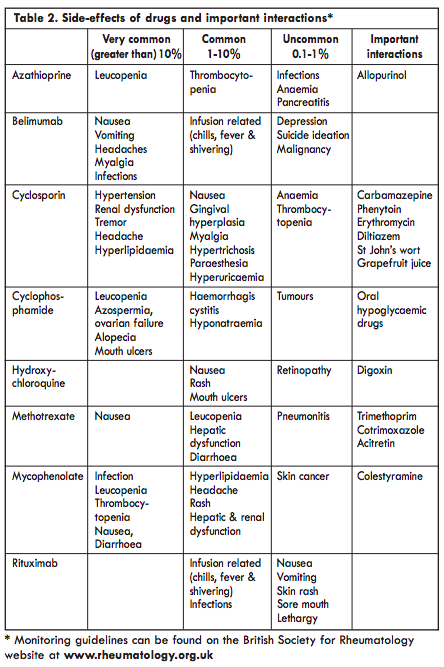

It is reasonable to divide lupus into mild, intermediate or severe disease, although even in mild disease symptoms such as malaise or arthralgia can be very disabling. The main therapeutic agents are shown in Table 2, although other drugs may be used in specific circumstances and are discussed in the relevant chapters. The management of clotting problems associated with anti-phospholipid antibodies and of lupus in pregnancy are fully discussed elsewhere in this book.

Mild disease

Common manifestations are fatigue, malar rashes, photosensitivity, mouth ulcers, Raynaud’s phenomenon, diffuse hair loss, arthralgia, myalgia and platelets 50-149x109/L. Often symptoms can be reasonably controlled by occasional NSAIDS and measures to reduce sun exposure, including the use of high factor sunscreens (high-SPF UV-A and UV-B). Hydroxychloroquine is recommended in this type of disease. Mepacrine can be a useful alternative to hydroxychloroquine or used in combination with it when the response is inadequate.Fatigue may be disabling despite control of other symptoms and may occasionally justify a trial of low dose steroid e.g. prednisolone 5-7.5mg daily, although results may be disappointing. Arthritis or rashes may respond to such doses but higher doses of steroid should generally be avoided in this type of disease since the risk of toxicity is likely to outweigh benefits. It is important to consider alternative explanations for fatigue such as anaemia, depression, a side-effect of medication or hypothyroidism, which is more common in people with lupus than in the general population. A healthy diet and regular gentle exercise should be encouraged.

NSAIDs can be effective for symptom control but should be used with caution for short periods of time (inflammatory arthralgia, myalgia, chest pain and fever) as they often cause an increase in blood pressure, fluid retention and can impair renal function. Furthermore, it now seems clear that both conventional NSAIDs (apart, perhaps, from naproxen) and the COX-2 selective NSAIDs can cause a modest increase in the risk of heart attack and stroke. As the risk of cardiovascular disease is increased in lupus, any additional risk should be avoided. They can also impair ovulation and, if used during pregnancy beyond the 20th week, can constrict the ductus arteriosus and impair foetal renal function.

Moderate disease

This category includes those with fever, more significant lupus related rashes, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia with scalp inflammation, arthritis, pleurisy, pericarditis, hepatitis and haematological manifestations such as thrombocytopenia and leukopenia. In such cases steroids are usually required. The aim is to use a dose sufficient to control the disease and then reduce it to as low a maintenance dose as possible. It is difficult to generalise regarding dose. Pleurisy can often be controlled by 15mg prednisolone daily, whereas, haematological problems may require doses of 30mg for disease suppression.Hydroxychloroquine may be adequate in conjunction with steroids but often immunosuppression is required. Azathioprine has been used most widely but in recent years methotrexate has been used increasingly as has mycophenolate mofetil. Ciclosporin can sometimes be useful, particularly in the treatment of thrombocytopenia, but because of its tendency to cause hypertension and to impair renal function it has to be used with care in lupus. All of these drugs take some time to take effect, e.g. 1-3 months, and during this period steroids will be required in a dose sufficient to control the disease. Once the patient is stabilised on the immunosuppressive drug every effort should be made to reduce steroids to the lowest possible maintenance dose or stopped altogether.

Severe disease

Significant pericarditis with effusionascities, enteritis, myelopathy, renal, CNS and severe skin or haematological disease fall into this category. The different subtypes and their distinct prognoses and treatments are discussed in more detail in the relevant chapters. In CNS disease, cerebral lupus has to be distinguished from clotting problems associated with antiphospholipid antibodies, as anticoagulation rather than immunosuppression will be required for the latter. Steroids will almost inevitably be required plus an immunosuppressive drug. Prednisolone 30mg day (rarely higher doses are needed) or pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone 500mg x 1-3 doses may be needed to bring the disease under control. Hydroxychloroquine is rarely adequate in this type of disease but is usually continued. Azathioprine, methotrexate or mycophenolate may be useful for their immunosuppressive and steroid-sparing effects. Mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide is used for lupus nephritis (LN) and for resistant, severe non-renal disease. The biologic therapies belimumab or rituximab are increasingly used for refractory lupus. Treatment can be divided into an initial induction phase in which active disease is brought under control, followed by a maintenance phase of less intensive therapy designed to keep it under control.

Cyclophosphamide was the mainstay of treatment for severe manifestations of lupus following landmark trials of the 1980s, especially for bad renal, CNS or pulmonary disease. This can be given as intermittent intravenous bolus infusions. The dose and frequency used will depend upon the severity of disease. However, a regime of 500mg of intravenous cyclophosphamide given every two weeks for a course of treatment plus initial pulsed intravenous steroid followed by oral steroids is often used. Mycophenolate is proving to be a less toxic and useful alternative to cyclophosphamide and has supplanted it in moderately severe cases and in many patients with renal lupus, although cyclophosphamide may still have a place in the induction phase of treatment in severe disease. If cyclophosphamide is used then transferring to mycophenolate, azathioprine or methotrexate for maintenance treatment should be done as soon as possible. The biologic therapies belimumab or rituximab may be considered, where patients have failed to respond to other immunosuppressive drugs, due to inefficacy or intolerance.

Additional treatments used in severe lupus include intravenous immunoglobulins, plasma exchange and several new therapies are under development. Intravenous immunoglobulin is used for thrombocytopenia but can be helpful for other manifestations. Plasma exchange is used rarely now but some clinicians believe that it can be helpful in acute, severe disease, particularly cerebral lupus.

Co-morbidity

It has become clear in recent years that lupus is a major risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease and that myocardial infarction and stroke are much more common in people with lupus than in the general population. As well as conventional risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, smoking and obesity, other factors are involved. These include antiphospholipid antibodies; endothelial dysfunction and lipid peroxidation in the vessel wall; use of NSAIDs and HRT, and steroid-induced diabetes. As well as seeking optimal control of the disease, it is imperative to check blood pressure and fasting lipids and glucose regularly, to institute appropriate treatment where necessary and to strongly discourage smoking in order to minimise cardiovascular risk factors.Comments on individual drugs

Steroids

The correct use of steroids is a key to the management of lupus. The disease may be under-treated but a more common mistake is to continue high dose steroids for too long. Mild disease may not require any steroids at all but if needed respond to less than or equal to 15 mg of prednisolone daily for 1-2 weeks then maintenance dose of less than or equal to 7.5mg daily with the disease-modifying drugs hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and methotrexate (MTX) and short courses of NSAIDs for symptomatic control. These drugs allow for the avoidance of or dose reduction of corticosteroids and steroid related side effects such as cataracts, osteoporotic fractures and cardiovascular damage. For arthritis intra-articular (IA) or intra-muscular (IM) injection of 80-120mg methylprednisolone should be used. For more severe disease i.v. methylprednisolone 500mg x 1-3 doses and/or oral prednisolone of 30mg per day is required to induce remission, either on their own, or more often, as part of a treatment protocol with another immunosuppressive drug. Every effort should be made to taper the dose to the lowest sufficient to maintain disease control. In patients who have had severe disease there is often a flare-up when the daily prednisolone dose is reduced to between 7.5 and 15mg daily. This should be borne in mind when monitoring someone with lupus and it is often wise to reduce the prednisolone cautiously when the daily dose is below 15mg.Steroid-induced osteoporosis is a common problem in people with lupus. National guidelines recommend that anyone who receives more than 7.5mg prednisolone daily for three months and is aged 65+ or has had a previous fragility fracture should receive osteoprotective treatment. Younger people should have their bone density measured serially by DEXA scan. We now have effective osteoprotective agents in the form of bisphosphonates (Fosamax, Actonel, Bonviva) and strontium ranelate (Protelos). HRT is no longer used for the prevention or treatment of osteoporosis because of the increased risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease. Although Raloxifene (Evista) reduces the risk of breast cancer it increases the risk of venous thromboembolism and has not been shown to reduce the frequency of non-vertebral fractures, so it is a poor alternative to bisphosphonates and strontium ranelate. It is not known whether treatment of women of child-bearing age with bisphosphonates poses any hazard to children born subsequently. Bisphposphonates are contra-indicated during pregnancy and it is recommended that pregnancy should be postponed for six months after withdrawal of bisphosphonates.

Increased susceptibility to infection is another major concern, especially in those who are also on immunosuppressive drugs. Steroids may aggravate hypertension, provoke diabetes and have an adverse effect on lipid profile which probably contributes to the increased cardiovascular mortality in lupus. In high doses steroids increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and will do so at lower doses when taken with NSAIDs. Osteonecrosis (avascular necrosis) is also fairly common in lupus and seems to be associated particularly with the use of highdose oral steroids or pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone.

Antimalarials

Hydroxychloroquine is generally preferred to chloroquine because the risk of ocular toxicity is believed to be greater with the latter. Ocular toxicity is related both to the daily and cumulative dose and the daily dose should be less than 5mg/kg of body weight. So long as this dose is not exceeded the risk of eye problems is very small. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists has recommended that patients requiring long term i.e. over 5 years of hydroxychloroquine should have a baseline examination in a hospital eye department ideally within 6 months of starting this therapy, but definitely within 12 months of starting therapy. Patients should be referred for annual screening after 5 years of therapy and be reviewed annually thereafter whilst on therapy. Hydroxychloroquine has the benefits of reducing cholesterol levels, a modest anti-platelet effect and it may reduce the extent of permanent tissue injury in lupus. Hydroxychloroquine appears to be safe in pregnancy and breast feeding.The addition of mepacrine 50-100mg daily (often 100mg on alternate days) may be useful in those not responding to hydroxychloroquine alone. Mepacrine is not thought to be associated with ocular side-effects.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine is an immunosuppressant antimetabolite: it reduces purine biosyn thesis which is necessary for proliferation of cells including those of the immune system. It is generally used in a dose of 1 2.5mg/kg. Nausea may occur while leucopenia and thrombocytopenia are seen in 4% of cases. Monitoring the drug can be a problem if people with lupus already have such clinical features. Abnormal liver function tests occur in a similar proportion of people. Azathioprine is catabolised by the enzyme thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) and about 1 in 300 people have a deficient genetic polymorphism of TPMT which renders them susceptible to drug toxicity. Laboratory testing can identify people at risk and so protect them from exposure to the drug, access to such testing is becoming more available. Azathioprine is considered safe to use during pregnancy in doses up to 2mg/kg.Mycophenolate mofetil

Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept) inhibits purine synthesis, lymphocyte proliferation and T cell-dependent antibody responses. Compared with cyclophosphamide it does not cause ovarian failure and is less likely to be associated with serious infection, leucopenia or severe alopecia. It is also probably more effective and better tolerated than azathioprine. It has rapidly assumed a central role in the management of lupus. It is contra-indicated in pregnancy and should only be used in women of child-bearing age in conjunction with reliable contraception. Because of its long half-life it should be stopped at least six weeks before planned conception.Methotrexate

Methotrexate is a folic acid antagonist with many effects on cells of the immune system including modulation of cytokine production. It is used in a once weekly regimen typically starting at a dose of 15mg per week building up to 25mg weekly if required. Folic acid 5-10mg once weekly (48 hours after the methotrexate) is routinely given to reduce the risk of side-effects. Nausea and mouth ulcers are fairly common and leucopenia, thrombocytopenia and abnormal liver function tests occur occasionally. Methotrexate is contra-indicated during pregnancy and should be used in women of child-bearing age only in conjunction with effective contraception. The drug should be withdrawn three months before conception is attempted.Cyclosporin

Ciclosporin inhibits the action of calcineurin and so leads to reduced function of effector T lymphocytes. It is used in a dose of 2.5-5mg/kg daily. Hypertension and an increase in serum creatinine are common and this makes it difficult to use in lupus where such features are often already present. Careful monitoring of blood pressure and creatinine are essential. It is considered reasonable to use it during pregnancy at the lowest effective dose with careful attention to blood pressure and renal function.Cyclophosphamide

This is an alkylating anti-neoplastic agent. It has been used extensively for the treatment of patients with lupus and internal organ involvement over the past four decades. It has been shown to improve the outcome of renal disease to a greater extent than steroids alone and is still widely used for the treatment of. severe CNS, renal or pulmonary disease. It is given as an intravenous infusion usually following the Euro-Lupus protocol (i.v. CYC at 500 mg every 2 weeks for 6 doses followed by oral AZA).The main hazards are rare but include increased risk of infection; ovarian failure; bladder toxicity, and increased risk of subsequent malignancy. The risk of haemorrhagic cystitis can be reduced somewhat by giving MESNA concurrently. Cyclophosphamide is teratogenic and impairs gonadal function in both men and women. Ovarian failure is closely related to the dose given and also the age of the patient: over 25 the risk increases significantly. In young people who want children subsequently storage of sperm or ovarian harvest and storage of eggs should be considered.The drug should be withdrawn three months before conception is attempted.

Intravenous immunoglobulin

This is a recognised treatment for refractory cytopenias, thrombocytopenic purpura, in pregnancy and patient with infections and can be helpful for other manifestations of lupus. The mode of action is unclear but saturation of Fc receptors and alteration of the idiotypic network are possible mechanisms. It is usually given in a dose of about 0.5-1g/kg as an intravenous infusion on three consecutive days and repeated at intervals depending on response. It can be used safely during pregnancy.Rituximab

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody which binds to the CD20 molecule on mature B cells and pre-B cells. CD20 is not, however, expressed on B cell progenitors or plasma cells, which means that the humoral immune system is not switched off completely. In early studies it was given in combination with cyclophosphamide but now it is often given with methotrexate. Following infusion of rituximab there is a sustained decrease in circulating B cells for several months but only a modest reduction in total immunoglobulin levels. Autoantibody levels tend to fall more than other antibodies. Rituximab has led to dramatic improvement in some people with refractory lupus and a repeat course of treatment has been effective in some of those who relapse. This agent is being studied in people with earlier disease and clearly represents a major therapeutic advance. Epratuzumab, a monoclonal antibody which reacts with another B cell antigen (CD22), failed to show significant benefit in phase III trials.Belimumab

Belimumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody directed against soluble B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS). It is the only NICE biologic agent approved as an add-on therapy for the treatment of adult patients with active, autoantibodypositive SLE with low complements levels who are receiving standard therapy. It is given as 10mg/kg infusion on day 0, 14, 28 and then after every 28 days. Treatment with belimumab has shown significant improvement in musculoskeletal, mucocutaneous, haematological, renal and immunological parameters. Belimumab is generally well-tolerated, common adverse effects include infections, infusion reactions, hypersensitivity, headache, nausea, and fatigue. Other adverse events include psychiatric events like anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and malignancies have also been reported. It is contraindicated in pregnancy.Other agents

In certain circumstances, other drugs may be needed to control specific disease manifestations, or when more commonly used drugs prove ineffective or are not tolerated. These include mepacrine, leflunomide, dapsone, thalidomide, quinacrine and clofazimine. These are discussed elsewhere in this book. A number of monoclonal antibodies and other biological agents which affect cells of the immune system or inhibit cytokines are being studied and it is very likely that additional agents will become available for treatment within the next few years.Conclusion

The management of lupus requires careful disease monitoring and interpretation of laboratory results and judicious use of the available drugs. It involves a constant struggle to strike the correct balance between under-treatment and overtreatment of the disease. Patients are often well informed about their disease and should be viewed as partners in disease management. Close collaboration between GP and specialist is essential for optimal disease management.Prof Chris Edwards

Consultant Rheumatologist

University Hospital Southampton

Tremona Road

Southampton

Hampshire SO16 6YD

Dr Madiha Ashraf

Rheumatology Research Fellow

Revised and updated from 2009 edition

by Dr Robin Butler

Consultant Rheumatologist

University Hospital Southampton

Tremona Road

Southampton

Hampshire SO16 6YD

Dr Madiha Ashraf

Rheumatology Research Fellow

Revised and updated from 2009 edition

by Dr Robin Butler

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)