Vasculitis

This site is intended for healthcare professionals as a useful source of information on the diagnosis, treatment and support of patients with lupus and related connective tissue diseases.

Introduction

Vasculitis means inflammation of blood vessels. Direct inflammatory changes within the wall of a blood vessel (i.e. vasculitis) frequently causes necrosis to the vessel wall, hence the term often used ‘necrotizing vasculitis’.Vasculitis can either be primary (e.g. polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis) occurring in the absence of a recognised cause or associated disease, or secondary to an established disease, (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus), or secondary to infection such as hepatitis B, C or HIV.

The consequence of vasculitis depends on the size, site and number of blood vessels involved. The spectrum of involvement ranges from relatively mild disease affecting small vessels or isolated to a single organ, to rapidly life threatening multi-system disease. When muscular arteries are involved they can develop focal or segmental lesions. Focal lesions indicate only part of the wall is involved which may become weak, leading to aneurysm formation which may be followed by rupture. Segmental lesions indicate that the whole circumference of the vessel is involved and is more common and this will lead to narrowing or occlusion with distal infarction. Haemorrhage into, or infarction of, vital internal organs are the most serious complications of vasculitis. Prior to the introduction of cyclophosphamide the mortality of the primary vasculitides, particularly granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was over 80% by one year. Improved treatment has dramatically improved the survival but there is still significant morbidity from the disease (and/or its treatment).

Classification

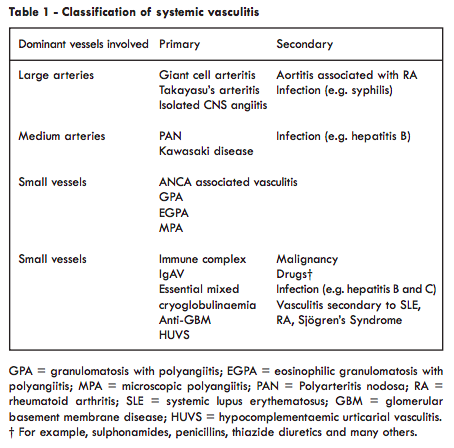

An understanding of the different types of vasculitis is helped by understanding classification. A number of different classification systems have been used, a favoured system being shown in Table 1 based on the dominant vessels involved and dividing diseases into primary and secondary vasculitis. Vasculitis occurring in the context of lupus is one of the secondary vasculitides and most commonly is associated with small vessel vasculitis but can involve small vessels and medium arteries when the consequences are much more serious (see below). The importance of this classification is that the different groups require different types of treatment.Agreed definitions of the various types of vasculitis have been produced by consensus and these define lupus vasculitis as - ‘vasculitis that is associated with and may be secondary to SLE’.

Epidemiology

The vasculitides are relatively rare. The primary vasculitides are, in general, conditions of the young and old. Childhood vasculitis includes Kawasaki disease, seen almost exclusively in children aged < 5 years. IgA vasculitis (Henoch Schönlein purpura) is predominately a disease of childhood and adolescence but occurs in adulthood. Giant cell arteritis, a form of large vessel vasculitis, is almost exclusively seen in those aged > 55 years. Skin vasculitis may occur on its own or be associated with internal organ involvement and is often triggered by infection and medication, it is probably one of the most common types of vasculitis. Severe multisystem vasculitis is rare and the overall annual incidence is around 40/million population. It has been estimated that the incidence of vasculitis in lupus is 3.6/million population which is as common as infection related vasculitis. When patients with lupus are assessed for the presence of vasculitis between 11 and 36% have evidence of vasculitis. Lupus patients with vasculitis tend to be male, have younger onset disease and longer disease duration than those without vasculitis. The majority of patients with vasculitis in lupus have benign disease confined to the skin, not requiring specific therapy.Pathogenesis

The vascular injury in lupus is thought to be mediated by immune complex deposition in vessel walls, which triggers an inflammatory cascade via complement activation. Biopsies show IgG deposition, complement components and fibrin deposition indicative of an immune complex mediated process.Clinical features

The clinical presentation of vasculitis varies dependent on the underlying disease. The most important organ involved in systemic vasculitis is the kidney. Any patient with suspected vasculitis should have dipstick testing of the urine and in the presence of systemic illness haematuria and proteinuria are important and serious prognostic signs. In those circumstances the differential diagnosis would include infection such as bacterial endocarditis, and malignancyThe most common clinical feature of lupus vasculitis is a skin rash. A non thrombocytopaenic purpuric rash often affecting the lower limbs may occur in 25% of patients. Other common lesions include punctate erythematous lesions on the fingertips and palms in up to two thirds of patients, other lesions include ulcers and ischaemic lesions, urticarial lesions and nodular lesions. A leucocytoclastic vasculitis may be shown on biopsy. Extracutaneous lesions may occur in up to 20% of patients with lupus vasculitis. Mononeuritis multiplex in over half of cases. Intestinal vasculitis of the ileum or colon occurs not infrequently.

Investigations

Investigations are directed towards confirming the diagnosis and assessing the extent and severity of organ involvement. In a lupus patient with vascular symptoms it is important to exclude thrombosis due to phospholipid antibodies and atherosclerosis.As indicated above, the single most important investigation in a patient with suspected vasculitis is urine testing. In a systemically unwell person the presence of blood and protein in the urine indicates the necessity for urgent referral and probably urgent treatment. Other investigations that can be helpful include a routine blood count and ESR. Anaemia of chronic disease develops quite rapidly in many vasculitides and most are associated with a high acute phase response as shown by a high ESR and/or CRP. Basic tests for renal and liver function are important to detect deteriorating renal function and mild derangement of liver enzymes is common in all inflammatory diseases including vasculitis, however, very high levels might indicate an associated hepatitis, such as hepatitis B or C infection.

Immunological tests are helpful. A low level of complement (C3 and C4) is often a feature of secondary vasculitis due to lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s Syndrome or infection, but is very rarely seen in patients with primary vasculitis. High levels of the appropriate antibodies are seen, for example DNA binding and Sm antibodies, in lupus vasculitis and rheumatoid factor in rheumatoid vasculitis. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are often present in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg Strauss) and microscopic polyangiitis; these conditions being known collectively as the anti neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitides. More specific tests include anti proteinase 3 antibodies which are strongly associated with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s), but ANCA with specificity against other enzymes, particularly myeloperoxidase, is often found in Churg-Straus syndrome and microscopic polyangiitis. ANCA may also be found in lupus but often with negative proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase antibodies. Other antibodies that should be sought include cardiolipin and beta 2 glycoprotein antibodies as their presence may indicate a thrombotic cause for vascular symptoms.

Investigations otherwise depend on the organ involved. Haemoptysis, which is common, requires a chest X-ray (possibly CT chest and pulmonary function tests) and nasal crusting or nasal discharge or bleeding indicates a necessity for ENT referral and sinus MRI or CT.

The diagnosis of vasculitis requires a tissue biopsy from an involved organ. Typically, this is skin or kidney but on occasions ENT, nerve or lung biopsy is necessary. If the clinical situation is typical and other conditions have been excluded, especially infection, it may be necessary to treat without waiting to obtain a confirmatory biopsy.

Treatment

Treatment of the vasculitides requires immunosuppression. The intensity of immunosuppression depends on the extent and severity of organ involvement. In lupus consideration may also need to be given to other non-vasculitis organ involvement. Severe multisystem disease requires glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide and the introduction of these agents has improved survival of the ANCA vasculitides to between 80 and 90% at 5 years. Less severe manifestations such as skin vasculitis may require therapy with glucocorticoids alone.Cyclophosphamide may be given by either the intravenous or oral routes. The intravenous route is preferred because it is as efficacious but is associated with less in the way of side effects. Patients requiring cyclophosphamide need to be monitored carefully, and patients with vasculitis need long-term follow up shared between general practitioner and the hospital because of the risk of relapse and toxicity from their treatment. The long-term risk is uroepithelial toxicity with haemorrhagic cystitis and bladder cancer. The role of other immunosuppressive and biologic drugs has been highlighted in the last few years with mycophenolate mofetil proving to be particularly useful for lupus nephritis. B cell depletion with rituximab has proved equally efficacious to cyclophosphamide in the ANCAassociated vasculitides and is now widely used. Its role in lupus vasculitis is less well established.

Conclusion

Recent advances in the understanding of the vasculitides have led to a dramatic improvement in outcome, increased recognition of the different types of vasculitis and an apparent increase in their incidence. Although rare, they are important because they are treatable and should and can be recognised and referred appropriately from primary care.

Prof Richard A Watts MA DM FRCP

Department of Rheumatology

Ipswich Hospital

Norwich Medical School

University of East Anglia

Revised and updated from 2009 edition by Prof David GI Scott

Department of Rheumatology

Ipswich Hospital

Norwich Medical School

University of East Anglia

Revised and updated from 2009 edition by Prof David GI Scott

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)

©2024 LUPUS UK (Registered charity no. 1200671)